Celebrating the 40th Anniversary of David Hounshell's _From American System to Mass Production_

Whelp. This newsletter has so far been slower than I hoped because, as soon as I launched it, health issues walloped me. This past weekend, however, the Business History Conference held its annual gathering in Providence, RI (wonderful place full of delightful old buildings, and I randomly bumped into a plaque dedicated to hometown boy, H.P. Lovecraft). At the conference, we held a panel celebrating the 40th anniversary of my doctoral advisor David Hounshell's great book, From American System to Mass Production, 1800-1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United States. The panel was conceived by my friend Professor David Kirsch (University of Maryland's Smith School of Business), whose book with Brent Goldfarb, Bubbles and Crashes: The Boom and Bust of Technological Innovation, you may have heard me trumpeting on other occasions. We were joined by Professor Sandeep Pilai (Bocconi University) who gave a fascinating talk suggesting that Hounshell's book had discovered the critical role of "scaling" in modern business and Professor Elizabeth "Betsy" Esch (University of Kansas), author of the important book, The Color Line and the Assembly Line: Managing Race in the Ford Empire, who explored the essential task of bringing labor, race, gender, and other crucial categories into histories of mass production. David Hounshell was also on the panel as a respondent. I am very grateful to all of the participants in the event, especially to its conceiver Kirsch who is such a kind and generous man. What follows were my comments there.

I want to begin by thanking my friend David Kirsch for originally conceiving of this panel. I want to do three things in my remarks here today: First, I want to talk about why this book, From American System to Mass Production, 1800-1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United States, remains and should remain such a vital text. Not all books retain the kind of power this one does forty years on, and I believe it is not only a model of where we have come from but also should be a model for future inquiry. I will say why. Second, I want to talk about how we might write this book differently today. And third, David's wishes that this panel be about his ideas and not about him be damned, I thought this was an appropriate moment to reflect briefly in a broader way on David’s career, so I will say a few words about what it’s like being a student of the author of From American System to Mass Production.

1. Beat One – Why From American System to Mass Production Remains So Vital

I have considered a number of hallways into this topic and have decided to go through a door that is broad and philosophical. Those of you who know me know that I have a substantial collection of hobbyhorses and soapboxes. These are fine, bespoke, handcrafted hobbyhorses and soapboxes, none of that tacky veneer stuff.

And one of my hobbyhorses in recent years is that, while I think cultural history, intellectual history, and the history of science have had much to teach the history of technology and business, so often in recent years when I hear talks or read work I feel like I am stuck in other people’s noggins. I feel like we’ve come to focus too much on noodle stuff. Like, I will show up for a talk that I think is going to be about technological change and instead get a plateful of deep exegesis about how someone imagined the future. You spend the whole time staring at the plate thinking you’ve gotten some hors d'oeuvres only to realize that there’s no main course coming. It’s like, you are going to tell me what actually happened and reflect on the important question of whether fantasy related to reality, aren’t you? No. You walk out the door still hungry.

You see, I am a materialist. I mean that in the sense of being influenced by Marx and Marxism as well as Weber, Bourdieu, and the entire tradition of what is known as conflict sociology. But I am also a materialist in a simpler sense, which is that I believe matter matters. If we are to understand human history, perhaps especially the deep transformations of the past 150 years, we must understand the ways in which humans learned to manipulate and understand matter, thereby remaking their world.

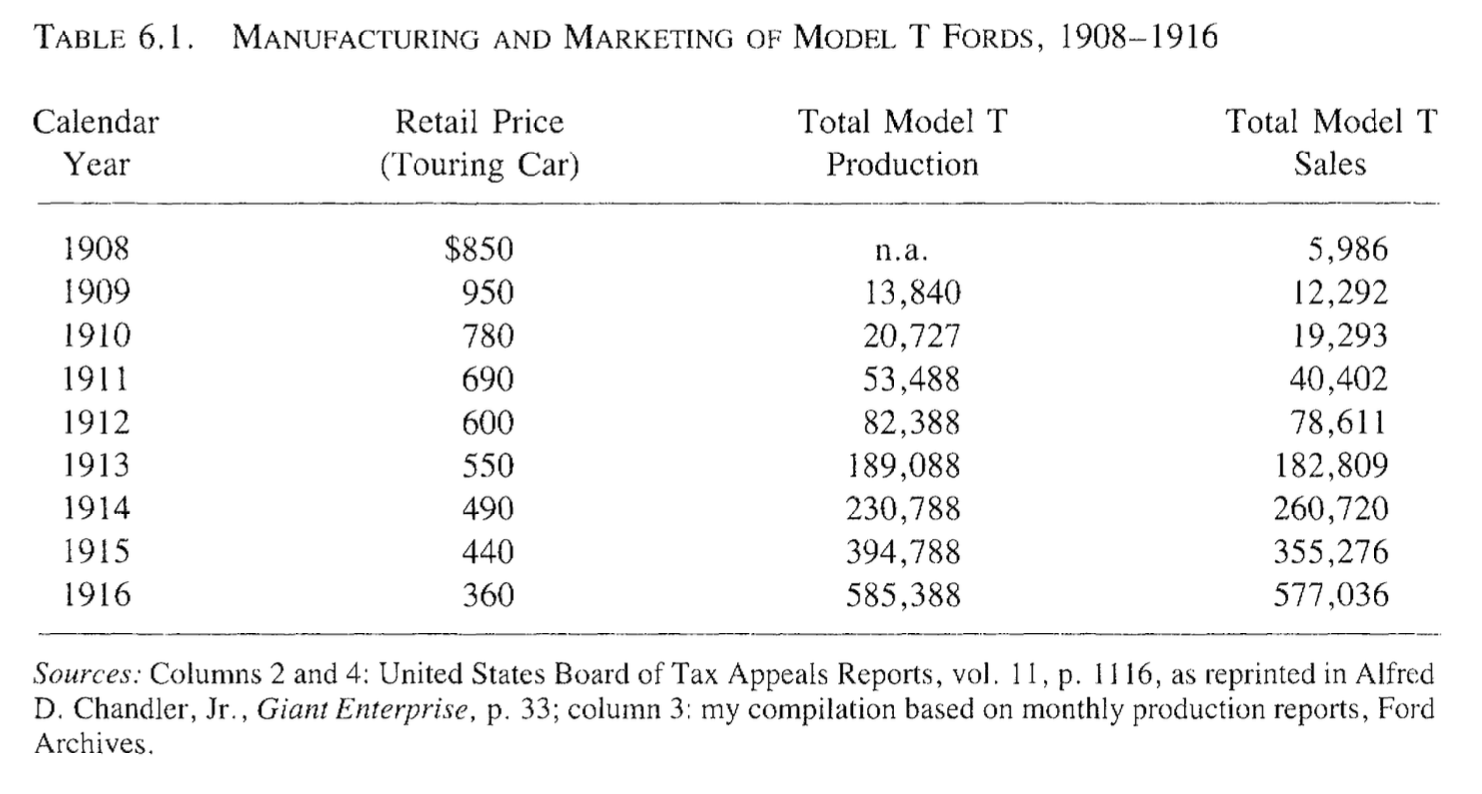

In my view, From American System to Mass Production, while perhaps not THE BIBLE, is certainly a scriptural text in such materialist history. The book works so hard to describe and understand the gritty, concrete changes that enabled the rise of mass production, one of the most profound shifts in all of human human history. This is not to say that the book gets all of the causes right, and Sandeep is going to poke at it from one direction here shortly. But still the text does so much to uncover the nature, reasons, and character of these deep shifts. For example, there is a table on pg. 224 of the book, titled "Manufacturing and Marketing of Model T Fords, 1908-1916," that I have used in innumerable lectures, talks, and writings. The table’s columns list the calendar year, retail price of the Model T, production numbers, and sales numbers. So here we go: 1909, the first year with complete data: the T costs $950, 13,840 were made, 12,292 sold. 1916, after the assembly line and so many other important changes have come along: $360, 585,388 made, 577,036 sold. [chefs kiss] If I’m in the right mood, it can actually bring a tear to my eye.

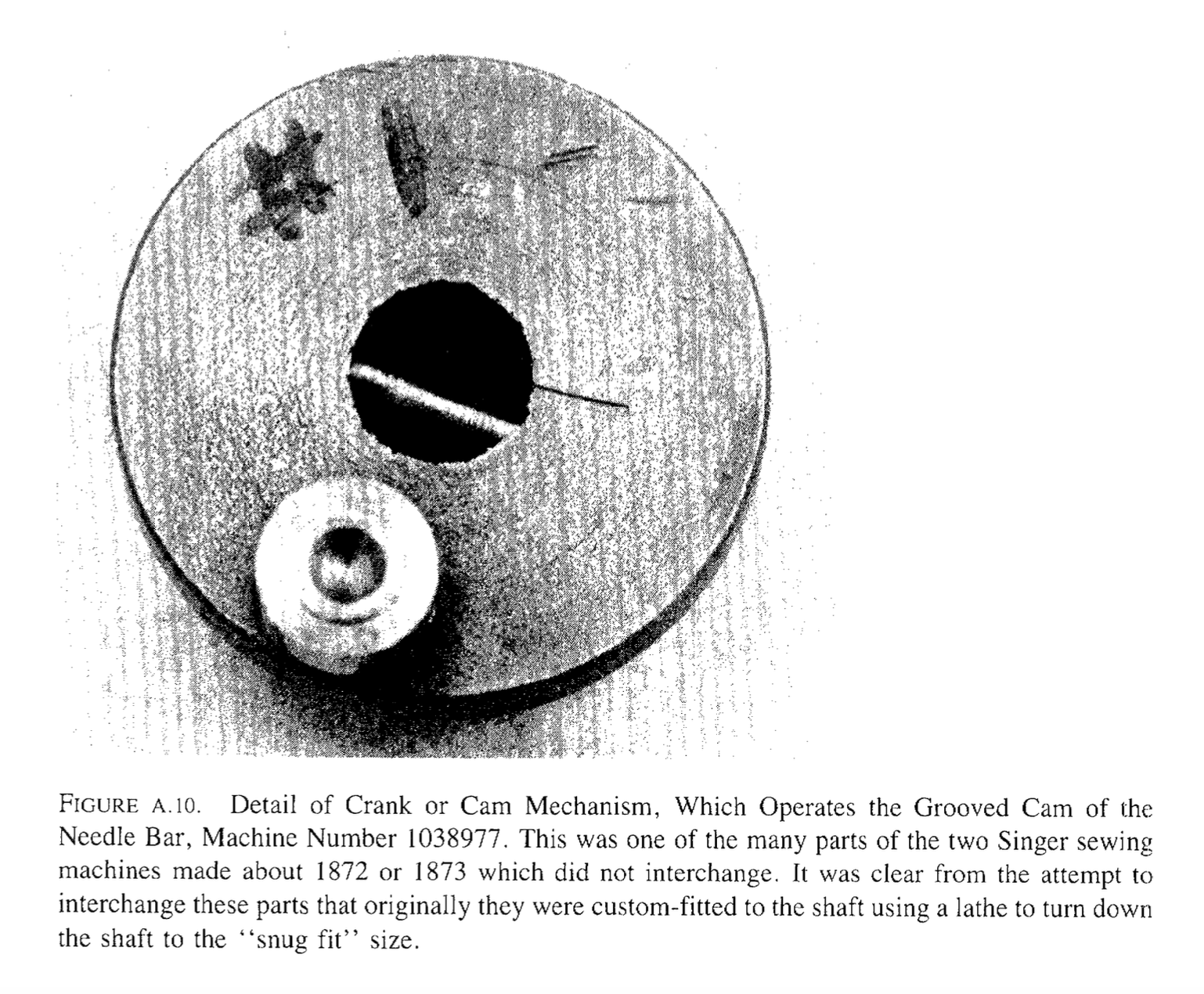

Perhaps my favorite moment in From American System to Mass Production comes not in the main historical narrative but in Appendix Two, titled Singer Sewing Machine Analysis. While David was a predoctoral fellow at the Smithsonian – and I think there’s something to reflect on here about the relationship between the history of technology and museums and material culture studies at that time – while he was a fellow, David somehow convinced people there to allow him to take apart two Singer sewing machines and attempt to move pieces between them and see if they were interchangeable, demonstrating unequivocally that they were NOT. The pieces would have required filing to be moved between machines. I mean, really, get more material than that. Just try. I dare you. As fans of the frequently-banned pornographic film, Gunsmith of Williamsburg, will tell you, filing, endless, endless filing, is the very heart of pre-mass production metalwork; filing is the antithesis of mass production; it is opposite of true mass production’s necessary but not sufficient cause interchangeable or spare parts, a topic that Phil Scranton is teaching us much about today.

When I talk to so many promising graduate students we are lucky to have in our community these days – people like Ella Coon and Ben Kodres-O'Brien of Columbia University and Sam Schirvar of Penn – I find them hankering for and doing materialist histories. This excites me and gives me hope, a rare commodity these days. But what should our signposts be in this quest? In so many ways, David’s book stands as a testament to materialist analysis of technological and business change and should be an inspiration to future histories that value this mode of analysis.

2. Beat two – what we might do differently today.

Now, let me just say that if I had to choose between changing something about From American System . . . and being able to read its sequel . . . I would absolutely choose the latter.

Still, I don’t think there is any doubt that if any historian, including David, was writing this book today they would do some things differently. Betsy is, I believe, going to talk about the topic of labor and workers and essential categories of race, gender, other identities, and their intersectionality, so I will I leave that to the side, though it is the theme I and many others today would naturally focus on here first. Here’s one thing that I’ve often wondered about, though: The book’s final chapter is titled “The Ethos of Mass Production and Its Critics,” and it covers critics such as Aldous Huxley, Charlie Chaplin, and Diego Rivera. The chapter has always been one of my favorites, but I often wondered what it could have been like if this theme of criticism and resistance rather than being treated as a separate topic at the end had been pulled forward and threaded throughout the text, so that movement and counter-movement became a part of the picture.

At the same time, From American System . . . is a book that is already full to the point of overflowing. Especially by today’s standards, it is long and very heavy, perhaps too heavy, on detail. So, often, when I think of other themes that might go into From American System . . . I think, well, either you are going to end up with a dad book history volume that belongs in the Oxford History of the United States, or what you have is another book. For example, we might think through the environmental toll of the rise of mass production, but that really is a different book and has been different books. Still, if I was going to add one theme to the book it would be that of use. In recent years, I have been influenced by another David - David Edgerton – in taking a use-centered perspective on the history of technology. So, to give an example, Priya Satia’s Empire of Guns: The Violent Making of the Industrial Revolution gives us some idea of what all those guns being made in British armories were being put to use for, particularly colonialism and dispossession. Even small glances of such use-based histories would be nice to see in From American System. But the question of what else we would do differently is one that I hope we will all discuss here together.

3. Beat Three – On Being a Student of the Author of From American System to Mass Production

David, for the past several months, when I thought about today, I wondered how I could adequately thank the person who has shaped my thinking more than any other human being, living or dead. I have concluded that I cannot do it. For two, maybe even two and a half years, I spent more than an hour, often two or three hours, in your office every week, where I was soaked in a firehose of history and historiography, the torrent of your incredible synthetic detailed memory. And this is what we talked about: how do we study, analyze, and – importantly – account for or find evidence about the history of the material world?

Now, when I started The Maintainers, some people saw it as an act of, like, oedipal rebellion against you and other mentors and friends like Steve Usselman who likes to put the word “innovation” in his book titles. And I’m not saying that take’s completely wrong. But, no, when people have suggested things like that to me, I tell them that they don’t understand. They don’t know, for example, that you and I spent multiple hours talking several times about the importance of maintenance in the history of technology, including memorably an extended conversation about Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. They don’t know that we talked about the research I was doing for Joel Tarr on maintenance practices in the manufactured gas industry in the Progressive Era, or that maintenance was a theme in my dissertation because of our conversations.

I wrote a dissertation and book deeply influenced by your thinking about regulation and technological change; I wrote about maintenance, something you and I spent hours discussing; and now I’m writing a history of American labor markets since the 1970s, focusing on themes of deindustrialization, various forms of industrial and innovation policy, and how organizations shift routines around new technologies, all themes we talked about endlessly. Wherever I go, you are with me. And in recent years your son, Eric, has also been one of my dearest companions on the road of life, another beautiful gift you and Nancy gave me, even if unintentionally. The time I spent with you was unbelievably formative for my life and thought to this very day. Everyone here knows how essential and meaningful learning is. My time with you was the most important experience of learning I ever had and will ever have. There is a reason when fellow Carnegie Mellon grad Susan Spellman and I talk about her relationship with her advisor Scott Sandage, who is also a dear friend and mentor of mine, we call him Brother, but when we talk about you and my relationship with you, we call you Dad

But here’s why this is worth saying and recognizing here at this gathering today: A set of personal virtues led to this great book’s virtues. That’s no doubt true of it’s vices, too. But your insistence on hard work, on precision, on clarity, on beauty, on high standards of thinking and especially of evidence – these virtues led not only to great works of history but also to you being a great teacher. My debts to you, David, including the ones you are currently accruing by housing 14 boxes of books in a rented storage container for me . . . my debts to you, David, are not ones that can ever be repaid but they are very real. And in that, I know I speak not only for myself but other students of yours as well, like Usselman, Steen, Goldstein, Holbrook, Gorman, Bugos, Asner, Burke, and so many others.

Now, those of you who know David, know that he is not a sentimental guy and he does not go in for the mawkish. My only defense is that, as the great sage Norm MacDonald once said, it’s not mawkish if it’s true, and it is true. But all of us here, myself included, want to focus on, probe, and even challenge the ideas of this great book, From American System to Mass Production, now forty years old, and so we are lucky to be joined by two scholars, Sandeep Pilai and Betsy Esch, who will help us do that in different ways. So Sandeep the floor is yours. Thank you.