In the Shadow of "Technology"

This is the first in a series of posts I hope to do over the course of the semester. One of the places where this series is driving to is an analysis and criticism of what I call Cultural Pessimist Technology Criticism - a tradition of thinking that blames technological change for cultural decline and that we find in the writings of people like Martin Heidegger, Jacques Ellul, Neil Postman, and a number of contemporary "technology critics," maybe especially Evangelical Christian ones. I believe this that tradition is muddle-headed, unfortunate, unduly nostalgic, and best avoided and that it's more influential today - including via writings on "solutionism" - than we might hope.

One thing we scholars in technology studies have to deal with is that the word "technology" is both a) of recent vintage and, a bigger deal, b) crappy.

Let's start with the crappiness first: "Technology" is famously a systematically vague term with lots of meanings - and a lot of those meanings are just silly, like the way so many people say "technology" but just mean their smartphone. For my money, I think the best work on this topic is Paul Nightingale's "What is Technology? Six Definitions and Two Pathologies."

This problem of multiple definitions is true of a LOT of words, of course, but is is a real issue for rigorous humanistic and social scientific inquiry that's aiming to do the best possible work. One strategy for dealing with the crappiness problem is to define the term when you use it, but this can be cumbersome.

A better strategy is the one employed by my something-of-a-mentor and friend, historian David Edgerton. As he explains in the second edition of his book, The Shock of the Old: Technology and Global History Since 1900, he used the word "technology" up through the writing of that book, but then afterwards hit upon the strategy of simply not using the word at all as an analytical term and "instead used more descriptive and specific terms, like aeroplane or machine tool, or the terms which were used in the past." (p. xii)

It seems to me that Edgerton's strategy is the one to take whenever possible. But one thing I have never found really is another one word term that allows me to point in the direction of what I care about and am interested in: the material dimensions of human and non-human animal life. So in lots of contexts, I find that I still have to rely on the word "technology," at least to get my foot in the door.

One thing the Edgerton strategy entails, though, and that I have talked about with him in the past, is that we only use the word "technology" when it is a term used by our actors, and even then we will need to do the important work of trying to figure out what the hell our actors were trying to say (while being attentive to the reality that sometimes bullshit-y vagueness is the point).

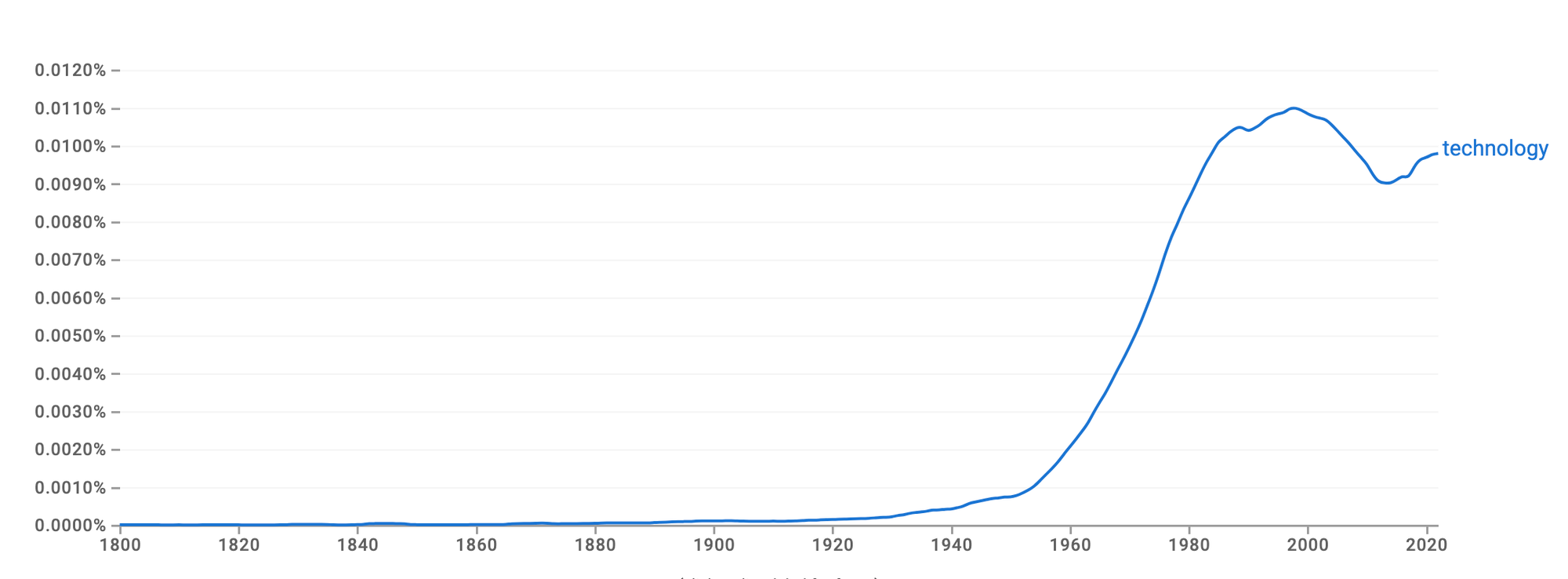

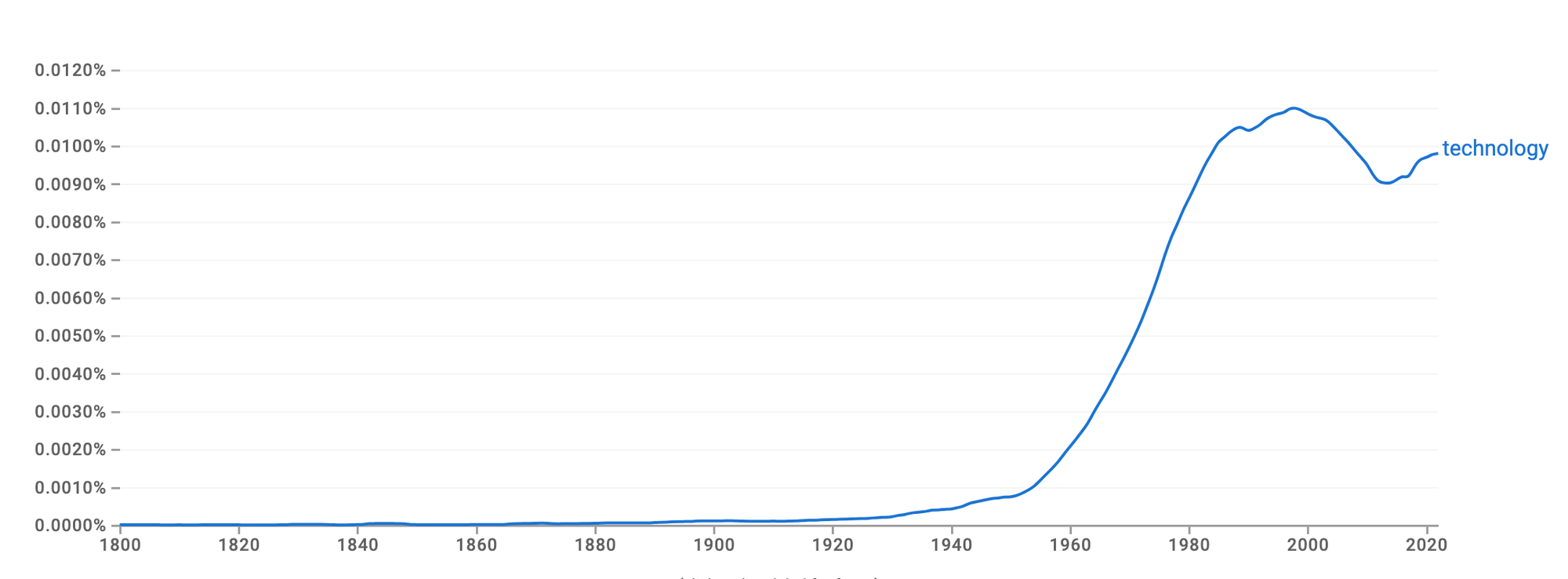

And this brings me to the problem of how "technology" is of recent vintage. For ease of reference, let me put that Ngram here again. Go ahead, take a moment. and ogle it.

Now, I think we are really lucky to have Eric Schatzberg's book, Technology: Critical History of a Concept, which recounts the history of the word and its relatives from the ancient world to just after World War II. You should read it, if you haven't. But one unfortunate aspect of that book is that it cuts off just as use of the word "technology" was taking off and becoming a mass phenomenon, which is why I've always hoped rumors are true that Schatzberg has a sequel on the way that would take this history closer to our present.

For the sake of brevity, I'm just going to assert something here: When you see the usage of a word take off like this, a lot of what people are using the word to say is going to be nonsense and bullshit. For sure, it could be pragmatically useful bullshit that has some effect in the world - like leaders talking about "technology" to rally the troops or win over investors - but there's still going to be a difference between what is being said and reality.

And this is a real issue for we technology studies folks: Especially if we are writing about things on the right side of that Ngram curve, in the tsunami like maw of that wave, in the shadow of "technology," we cannot take for granted that talk of "technology" has much of anything to do with actual material reality, or at least that it may not reflect strong knowledge of the material world. Among other things, what all of this entails is that the people we are studying are going to attribute power and social and economic changes to "technology" even when it is inaccurate to do so. Moreover, you can't see the truth of this gap by only studying discourses or doing intellectual history. You have to get outside of those documents and try to find sources that will allow you to guess what was going on materially to the best of your ability. (I will be talking a lot about this in forthcoming posts - intellectual historians, prepare your hides for some smacks.)

One way of talking about this gap between ideas and talk, on the one hand, and the world, on the other, is through the term ideology. My sense is that if we look back on the past several decades of technology studies broadly construed we find a lot of people writing about the ideology of "technology" and its history. For example, John Staudenmaier's book, Technology's Storytellers, which is a history of the history of technology, both examines the work of people who were attending to the ideology of "technology" and does this kind of work itself. And I think we can multiply all kinds of examples. Like, when I was in grad school, I enjoyed and was influenced by Paul Edward's book, The Closed World: Computers and the Politics of Discourse in Cold War America, and Gabrielle Hecht's book, The Radiance of France: Nuclear Power and National Identity After World War II, both of which are, in different ways, about ideologies of "technology." Edgerton is one of the greatest masters we have on this topic. Several of his essays as well as Shock of the Old are acerbic eviscerations of the hot sloppy mess that is talk of "technology." (Ch. 1 of Shock is a good starting point.)

And one of the great and most important things that's been happening in recent decades in technology studies is that folks have been broadening out to understand how people all over the world, especially in non-US, non-EU nations. And there's a tradition here, too. We can think of early works like Michael Adas's Machines as the Measure of Men: Science, Technology, and Ideologies of Western Dominance (1989). And it says something about Edgerton's breadth as a thinker that he's important here, too - again, see Shock. But what we have in recent years is a multiplication of scholars examining how people thought about technological change, economies, and other materialist topics, including both in their own native terms and via terms that spread quickly around the globe during particular periods, like "import substitution." I'm thinking of folks like Hyung-Sub Choi, Lilly Irani, Clapperton Mavhunga, Fabian Prieto-Nañez, Laura Ann Twagira, my doctoral advisee Panita Chatikavanij, Fernanda Rosa, Verónica Uribe del Águila, Jennifer Hart, Josh Grace, and many others.

Again, one thing historically examining the ideology of "technology" will often show us is that there is a gap between what is thought and said and what actually fucking happened. In The Innovation Delusion, Andy Russell and I relied on a distinction between what we called innovation-speak, or thoughts and ideas about innovation that emerged from the post-World War II period to the present, and actual innovation. And we needed this distinction because so much innovation-speak has demonstrably little to do with actual processes of change. I think we have to make the same kind of move when it comes to the word "technology," although I have no desire to engage the clunkiness of constantly referring to technology-speak versus actual technology.

I think we could come up with a number of different ways of describing and taxonomies for characterizing the gap between the ideology of "technology" and actual mothafuckin' material reality. But to end here, I want to focus on an axis that we might think of as having two poles - boosterism and criticism - both of which have their fill of people who talked a lot but did little work to understand the world around them. (If you have read some of my earlier work, you will see that these two poles mirror, in some ways, things I have written about hype and criti-hype) To be clear, terms like booster and critic are simplifications, and we can get into a whole different kind of trouble if we take terms like these too seriously (as we see these days with the whole discourse around "doomers"). The point is to sensitize us to the fact that the gap between "technology" and material reality shows up in the world in a variety of ways.

Boosters: If you spend a lot of time reading a great number of primary sources featuring the word "technology" from the 1950s through the present, the way I have, you're going to find yourself reading a lot of people who are pretty high on and excited about the potentials of technological change and who are trying to figure out how to get more of it. They are boosters for various causes related to "technology," and they are using the word "technology" to try to win folks over to their sides.

Beating up on such stuff is basically the bread and butter work of what is called "technology criticism" - or more cringe-ly, "tech criticism" - and related forms of communicating. But because boosters are often bullshitting people, in Harry Frankfurt's sense of being more concerned with winning people over than with truth or falsity, this is indeed going to be a reliable trove of significant gaps between talk and reality.

We could list oodles of examples here. But one I have been focusing on recently has to do with Robert Reich's time as Secretary of Labor in the Clinton Administration during the moment of "the New Economy." As I show in an essay, Reich fell hook, line, and sinker for the 1990s idea of "the New Economy" and, in particular, for the notion that technological change, mostly in the form of digital technologies, was radically remaking the economy in ways that called for the working classes getting new kinds of skills. (As Daniel Greene has shown in his good book, The Promise of Access, this was also the basic idea that undergirded talk of "the Digital Divide" during that period.) Reich's version of this notion involved talking a lot about "technicians" and related technical jobs, and he claimed before Congress and in other places that technician-type jobs were the fastest growing job categories in the United States. But as Doug Henwood first pointed out in his wonderful rant of a book, After the New Economy, Reich's claims about technicians was simply not true. In fact, publications during that time out of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which was a part of the very agency Reich was nominally in charge of, showed that the fastest growing job categories in the United States were two kinds of home health aides, a horribly underpaid and stressful job, and other several other kinds of low-wage roles. Reich was so enamored with a popular story about "technology" that he missed reality, and I believe this misunderstanding also led to Reich making bad policy recommendations during his time as labor secretary. Misunderstanding is bad not just because it makes us look stupid but because it leads to actual harm.

Critics: But boosters aren't the only people who misattribute power to "technology." Critics do this too. I'm not sure what I think about Matthew Yglesias in general, but I thought this tweet could be read as a hilarious joke about "tech critics" who make such an error.

Guy who thinks housing is cheaper in North Carolina than in Massachusetts because NC has done a much better job of cracking down on algorithmic rent setting.

— Matthew Yglesias (@mattyglesias) September 13, 2024

Increasingly, my sense of things is that we see a lot of misattribution of power to "technology" in criticisms today of "Big Tech," social media, and, sadly, algorithmic bias, too. But my key example here is what I call Cultural Pessimist Technology Criticism, folks like Jaques Ellul, the Frankfurt School, Neil Postman, Langdon Winner, who I will be writing about in future posts. My argument will be that these folks make claims about the powers of "technology" that are unrealistic and unsupported by evidence, and that truly materialist forms of criticism will not fall into these traps.

The core thing both bad criticism today and lousy criticism of the past share, it seems to me, is a lack of empiricism. Not only were people like Langdon Winner and Neil Postman not getting off their rear ends and doing their own research, they also weren't doing the kinds of "library-based" research one needs to do to draw on others who ARE doing empirical work to try to understand what is happening in material reality. The worst thinking arises from inhaling our dyspeptic flatulence and mistaking the mind-bending results of those fumes for looking at the world. (Someday maybe I'll put up a post that draws on lots of philosophical and spiritual wisdom traditions, especially from Asia, simply titled "The Person Who Is Most Likely to Gaslight You Is Yourself.")

Now, you might ask, "Why should we go after these critics?" because you feel like you are on their side in some deep way. But I think this is a mistake. Not a little mistake. A BIG ONE. The most important thing of all in technology studies is that we find the best possible ways to think about and study the material dimensions of human and non-human life, and we can't do this if we are using bad models or have a bunch of unexamined cruft in our noggins. Critical thinking must begin a home.

If you have thoughts about what I wrote above, I would love to hear them. For now, I will say in the next post in this series I will ask the question, Is "Solutionism" a Causal Force in Social Reality? And I will say that I am open to argument, but, for now, my answer is, kinda doubt it. And in the post after that, I will argue that works that center on the idea of "instrumental reason" are probably best avoided, including because they contain thinking errors that lead us astray.